When you think of great artists of the Renaissance, who comes to mind? Perhaps Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael? Donatello, Caravaggio, or Bellini? My guess is that a German artist known mostly for his woodcuts is not the first to pop into your head, but Albrecht Durer is undoubtedly one of the greatest artists of the late Renaissance.

Durer was born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1471. This was a time of great change and discovery in Europe. Renaissance means “new birth,” and that’s truly what this time was. It seems like world-changing events were taking place nearly every year. Martin Luther was born in 1483, Columbus discovered the New World in 1492, and perhaps most notable for young Albrecht, Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1440.

Durer’s father was a goldsmith, and his godfather was a printer and publisher. One of his godfather’s publications, the Nuremberg Chronicle, used hundreds of woodcuts to portray the history of the world, some of which young Albrecht may have worked on. His first significant work to be published was a woodcut which served as the title page for a volume of St. Jerome’s Letters in August of 1492.

The zeitgeist into which Durer was born was one of advancement as well as apocalypse. Religious and political change was on the horizon. The plague had continued to afflict the continent. Out of 18 children, Albrecht was only one of three who survived into adulthood. With the year 1500 approaching, a sense of fear and dread began to seize the masses. Durer felt this as well, and in 1498 he published the volume Apocalypse, a series of fifteen woodcuts portraying scenes from the book of Revelation. The most famous of these being The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and St Michael Fighting the Dragon.

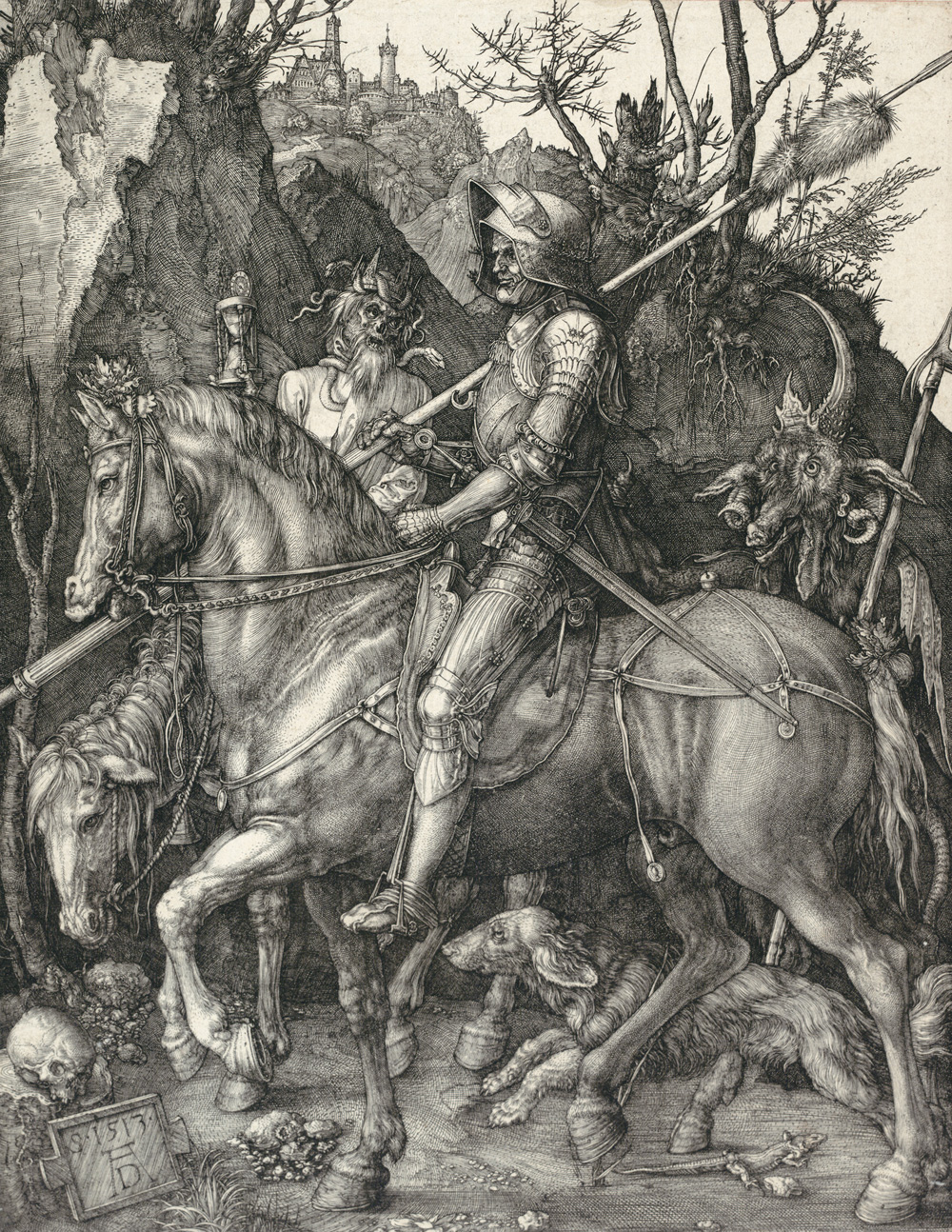

Another work with an end-times theme, Knight, Death, and the Devil, came about as the first of his series Meistertiche (or master prints). A knight rides confidently through a narrow valley surrounded by a demon and a figure of death riding a pale horse. Up above, a mighty fortress perched on a hilltop beckons the rider to endure and persevere through all the evils of this world to finally reach the eternal kingdom of God. It’s Durer’s medieval take on the line from Psalm 23, “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.”

Durer seemed to be quite interested in Martin Luther and the Reformation. He mentioned Luther several times in his writings, and he appears to have received a copy of Luther’s Babylonian Captivity of the Church in 1520. He also wrote of his desire to draw Luther in his diary from 1520: “God help me that I may go to Dr. Martin Luther as I intend to make a portrait of him with great care and engrave him on a copper plate to create a lasting memorial of the Christian who helped me overcome so many difficulties.”

Durer died in August of 1528 at the age of 56. His monogram, a stylized AD, was a sign of his initials and a symbol of the Latin phrase “Anno Domini,” the year of our Lord. It is now a lasting memorial of the immense talent of this incredible artist and the God of all grace who inspired his work.

+++